Impacts of CPVA

Living with CPVA means that all family members must adapt their own behaviour and responses to cope with and respond to the violence. Parents sometimes feel they cannot be the parent or partner they want to be. For example, their focus is predominantly on the child using violence rather than their time shared amongst their other children.

Many people don’t believe or understand how a child can be in control of the parent. This adds to the invisibility of CPVA in New Zealand and families become socially isolated, unable to share what is happening to them with friends or professionals. Some whānau, family and friends may not understand the severity or seriousness of the situation and unintentionally minimise what is occurring or provide advice to use parenting strategies to restrict or punish children.

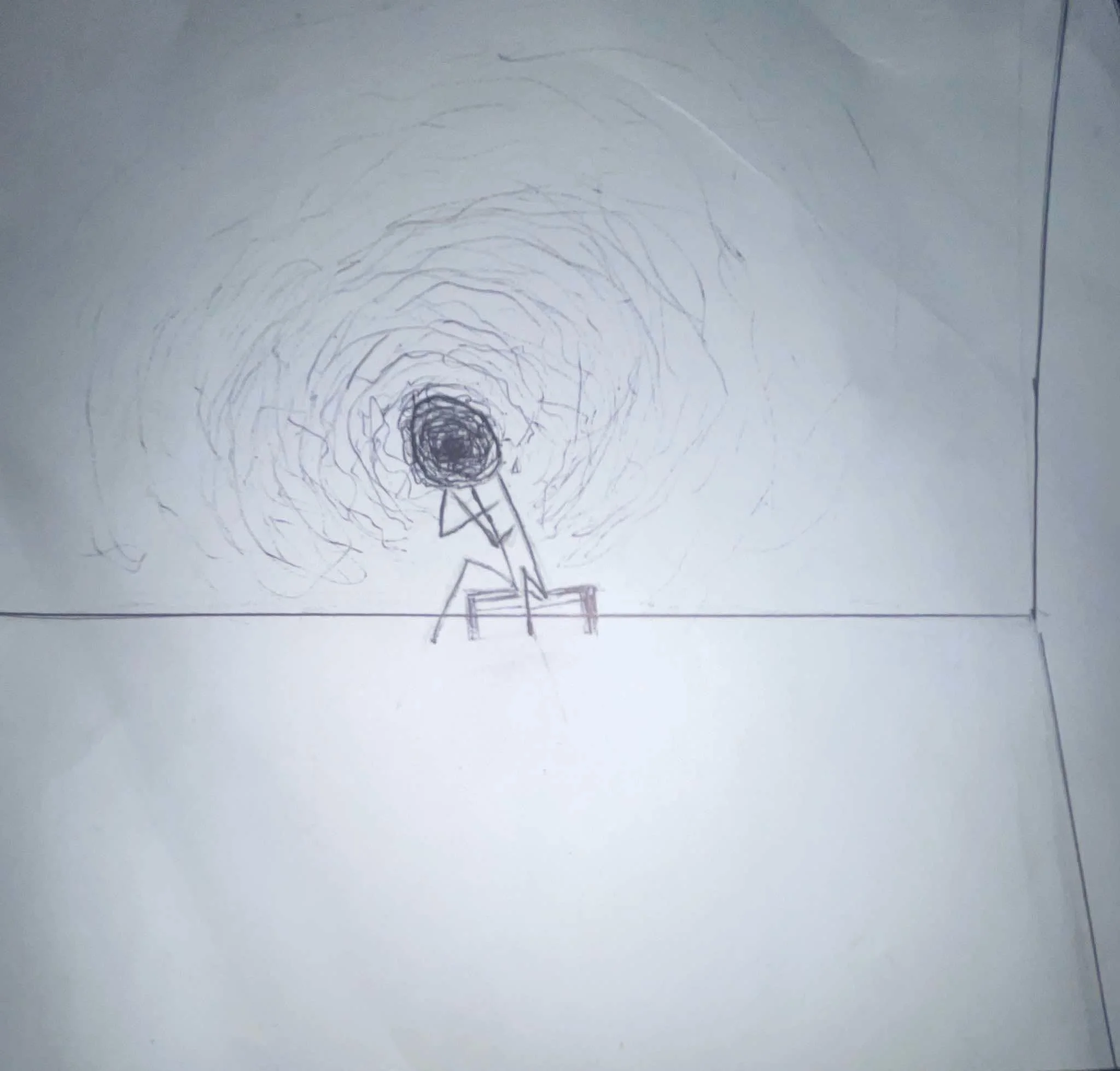

This is a drawing by a sibling who has grown up with Child to Parent Violence in their family/whanau. It shows a stick person sitting on a bench in an empty room. The person is holding their head in their hands with darkness over their face and multiple lines circling out from their head, symbolising the mental distress caused by growing up with violence from their sibling.

“Unless people have directly experienced the constant pressures of raising a child with complex behavioural needs together with coercive control, it is hard to relate to how devastating and traumatic this is for the parents/caregivers as well as the child. Loss of hope, shame, blame isolation, suicide ideation and failure are in the mix alongside deep love and despair.”

Parents

Parents living with CPVA have increased risk of suicide ideation, poor health outcomes, depression and anxiety. They have reported feeling:

Unsafe

Frightened

Isolated

Helpless

Frustrated

Guilty

Ashamed

Humiliated

Worried.

Siblings

Siblings can find it traumatic witnessing parents being assaulted and abused. They may also be hurt by violence directed towards them.

At times, they may try to intervene to protect their parent, or use violence to harm their sibling in retaliation (i.e. to get their own back), or withdraw themselves from the family.

Siblings may also experience difficulties being assertive as they have “walked on eggshells” throughout their childhood.

Children

Children who use violence experience low self-esteem and reduced emotional resilience.

They may sustain injuries to themselves (intentionally or unintentionally), have poor relationships with family and whānau which could result in being placed into the care of Oranga Tamariki, or entering the youth justice system.

In adulthood, they have an increased risk of substance misuse and involvement in intimate partner violence.

Contributing Factors

There is a broad range of contributing factors to CPVA. Some of the more common factors are:

Children who experience adverse childhood experiences (ACES) are more likely to experience difficulties self-regulating. They may rely on aggressive and disruptive behavioural responses as a protective mechanism.

Trauma and prenatal exposure to alcohol and drugs can impact the developing brain, resulting in challenges with emotional regulation and impulse control.

School can be particularly stressful for parents and their children. Many neurodivergent children do not get the support or attention they need (due to under resourcing, poor funding, lack of knowledge of neurodivergence, etc) resulting in high anxiety levels. This can contribute to the violent behaviour at home. Children who use CPVA may be disruptive at school which creates a risk of them being excluded.

Substance misuse can lead to a deterioration in mental wellbeing and affect impulse control and emotional regulation. Children may also use coercion and violence towards their parents to access money for substances.